Tesla Agile Success

The main reasons behind Tesla’s success analysts and short sellers overlook, and what competitors should look at to avoid being left behind.

On September 22nd 2020, Tesla battery day was inspiring and exciting, it showed the scale of technological progress Tesla spearheads. Yet, what was truly impressive was not so much the technology itself but what it showed about how Tesla works, how they think about their products and means of production to keep improving both.

Leaders in any industry shall watch the video. More broadly, for anyone aiming to improve their organisation, Tesla battery day was full of essential learning on how to better work collectively.

Video link is here, starting at the battery presentation: https://youtu.be/l6T9xIeZTds?t=2026

In this paper we also repeatedly reference to the content of a discussion between Elon Musk and Sandy Munro: Elon Musk Interview: 1-on-1 with Sandy Munro

This is no usual organisation

From the moment Tesla announced their new Gigafactory in Shanghai, till the end of 2019, many bears, critics, industry experts and analysts claimed the timeline was unrealistic. They compared Tesla plans to what the car industry had been able to achieve. Here is a brief extract from one of many such articles, published in February 2019:

“The history of auto manufacturing plant construction stands in stark opposition beside Tesla’s claimed timetable. With little in the way of activity on the ground on recent inspection and external financing not yet secured, it is hard to see how Tesla can keep its promise of achieving volume production in less than 11 months.

Even with the experience, expertise and resources of a major automaker, Tesla’s timeline would appear extremely implausible – at best. Of course, no major automaker would even attempt such a feat, given the added cost and risk involved in accelerating a timetable to such an extraordinary degree.

Auto plant construction is a meticulous and complex affair that usually takes multiple years to complete.”

Established competitors would need years to create such a factory, therefore, by analogy, Tesla plans were unrealistic. Simple, yet proven wrong when the first cars were produced there at the end of 2019, with production ramping up in early 2020. Even more, Tesla keeps learning and improving: although Giga Berlin suffered delays mostly due to ecological concerns, Tesla use even faster methods than in Shanghai to increase factory construction speed.

It’s not just Tesla, it is also true for SpaceX. About a decade ago, when SpaceX started and wanted to create reusable rockets, then leader Arianespace said they had looked at reusable rockets technology and did not believe it was ready for industrialisation. Fast forward some years later, SpaceX indeed managed to create and operate reusable rockets, and Arianespace was left asking European governments to commit to use the more recent Ariane 6, cheaper than previous Ariane rockets, however still pricier than SpaceX options and still not reusable.

Analysts and industry experts mostly look at Tesla from the prism of how others in the industry work. As mentioned before, they were proven wrong. Then, unable or unwilling to look further than analogies, many started to say that Tesla is more of a software company than a car company, therefore it should be compared to other actors in the web and software. Indeed, Tesla’s efficiency and ways of working are more aligned to the software big names than legacy car companies. It is often written that Tesla has a few years of advance on its competitors, yet what really matters is not so much the current advance itself but how they achieved this advance. What really matters is how, with inferior resources, they managed to innovate faster and create better products that customers love.

How can Elon Musk companies repeatedly pioneer and achieve things those larger historic competitors could not?

Passion and dedication over diploma

The first thing you see, when the Battery Day presentation starts, is how the speakers are dressed: very casual. As with the Silicon Valley trend iconised by Steve Jobs’ famous black turtleneck T-shirt, your smartness and importance at Tesla are not based on how you look, but on what you do and how you work with others. Readers working in such a company will likely think “well, that’s obvious, why would you even judge professional qualities on someone’s appearance?”, yet it is still the way in many organisations.

What transpires from Tesla presentation, especially when they involve many mostly younger colleagues at the end of it to speak about their own specialized work, is that this is a place with an attractive environment and work culture, which is confirmed in the list of most attractive companies for young engineers. You can feel their passion, their involvement, their pride of being part of it, working for a project to better our world, rather than working only for a salary.

You can see also how they encourage people to join them: it is not “if you have the best diploma”, but rather “if you are as motivated as us to push forward technical progress and innovation to achieve our company mission, join us!”. Tesla employees start work with a 4-page employee handbook titled “Tesla Anti-Handbook Handbook” that says they are fully empowered, anyone can do anything, and anyone can talk to Elon Musk. Elon went further to publicly indicate that if an employee tries to stop another employee from communicating up passed them, they will be fired.

Diploma are too often listed as a condition on many job offers, not so much at Tesla. We took a random offer on their website, for an Electro-Acoustical Design Engineer. In the requirements section, it is written “Masters in Engineering, or proof of exceptional skills in related field, with minimum 10 years of experience developing audio products from scratch”. You need the skills, but if you acquired them on your own and do not have a diploma, it is very much ok too.

ttps://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1324283305789812736

While advertising for Giga Berlin hiring on Twitter, Elon Musk said he would interview engineers in person, and asked candidates sending their resume to “please describe a few of the hardest problems you solved & exactly how you solved them”. The focus is on problem solving and finding better ways to do things. It is not surprising, since Tesla faces multiple technological challenges to achieve its mission, therefore problem solving and continuous improvement are not nice-to-have but conditions for success.

Relatedly, Elon said in a Wall Street Journal CEO summit that “there might be too many MBAs running companies”, and that CEOs should be more focused on the product or service itself. He recommends to spend less time on board meetings and on financials, but more time on the factory floor and with their customers, because what matters at the end is to make great products. He also said that “path to leadership should not be through MBAs and business schools. It should be work your way up, do useful things, [rather than being] parachuted as the leader [while you] don’t actually know how things work.”

Of course, not everything has been positive about Tesla: the company has not been a happy land for all of its current or past employees. There have been well publicised difficulties for employees to unionise, a lot of extra hours demanded especially in “production hell” for model 3, out-of-contract tasks such as delivering cars to clients, and a number of high-profile departures over the years. Yet, overall, for a company that grew that fast in an industry where it was deemed impossible for a new player to emerge, Tesla has done incredibly well.

Company mission: make the world a better place

Inspiring and difficult, those are two aspects of Tesla’s mission. Too often employees do not know their company’s mission, some companies do not even have one, or the mission is mostly financial.

Tesla is a different breed of business. As Elon Musk said in the Battery Day presentation, the goal is not money, the goal is helping the world transition away from limited and climate changing fuels towards renewable energy. Money is an essential tool, and a necessary pleasant consequence of good business, but it is not the goal. This is reflected in Tesla opening most of its IP, and when Elon says being profitable is necessary for the company to keep going, but the goal is really to increase the speed of the ongoing transition from gasoline engines to electric cars.

At Tesla, product goals are set as progress towards what is possible under the laws of physics. Joe Justice, who worked at Tesla, said there is no competitor to benchmark but a focus on how much progress is made toward what is ultimately achievable in physics as we understand it. This is well summarized by, ironically, a senior Daimler (Mercedes Benz) engineer: “We asked our engineers to shoot for the moon. [Elon] went straight for Mars.”

As a result, Tesla can attract talents who not only want to make money but also, essentially, want as much to feel that what they do, what the company they work in does, has a meaning, that working there is both satisfying, rewarding, and good.

Innovating faster

The company’s mission strongly influences how people work. For Tesla, it is so ambitious that they know they cannot achieve it without major technological breakthroughs. Elon notably said that “pace of innovation is all that matters in the long run”.

In the book “Team of teams”, General McChrystal describes how military methods were insufficiently efficient to defeat the insurgency movement in Iraq post-2003. While the military methods had proven successful against pyramidal organisations, this insurgency was made of a network of rapidly adapting, self-organising autonomous cells. As a consequence of it, increasing efficiency of existing systems was by far insufficient to achieve the mission, and the General and his teams had to profoundly rethink how they operated. Tesla has constantly faced similar challenges as usual industrial methods and organisational set-ups were insufficient for them to grow and be successful against established, well-funded competitors: they had to be better and faster, do more with less. Speaking on camera from SpaceX’s Starbase, Elon said a key principle is to focus on what knowledge can you learn in the shortest period of time.

Over the last five years, Tesla had a tumultuous life-or-death rapid expansion, getting close to going bankrupt as the ramping up of Model 3 did not go as smoothly as expected. Yet, with lower investment than their larger established competitors, they managed to bring noted innovations that have surprised industry experts. Among the most recent ones: designing the battery casing as a part of the car structure, the giga press, the octovalve and its manifold, and enhancing their car seats from being the worst in early model S to the best on the market (according to industry veteran Sandy Munro).

The most talked about in the media, because of its sheer size, is the giga press. It enables Tesla to create larger parts of the cars body, such as with the front and rear parts of the model Y. Elon said the model Y rear part produced by the giga press at their Fremont factory reduced the body shop by 30% compared to Model 3, or about 300 less robots.

Another innovation that got a bit less attention yet is as impressive, is the octovalve.

Cooling and heating systems are rarely centralised in a car, with much duplications. When Sandy Munro looked for the first time at the Octovalve, he thought this was a brilliant piece of engineering, saving space, reducing weight, complexity and thus quality risks, and cars electric consumption by up to 20%. He mused that there had not been such a radical improvement in the industry about cooling and heating for decades.

How is it that Tesla have been able to generate more radical innovations than their established competitors, while until a few years ago they had lower R&D budget than all the big brands around? That question should be at the core of most competitors’ concerns.

First principles and system design

How Tesla achieves higher pace of innovation with fewer resources is mostly based on two factors: “first principles”, and the way people collaborate, how the organisation is set up.

The “first principles” approach is powerful: look at the whole system to understand its fundamentals and see how you could refactor it and make it better.

This is well exemplified in the Battery Day presentation section about the nickel value chain: rather than joining a cohort of clients dealing with mining companies in the same way it has been done for decades, Tesla looked at the whole value chain, from the ore in the ground to the incorporation in batteries, and realized the current value chain is slow, wasteful and expensive. They therefore opted to refactor it, and that is what they showed here. It is brilliant, and much simpler! In fact, in the future, people will question why it took so long to happen, as it looks so obvious once it is done. As Elon says, it is complicated until it is done, then it is simple.

Another impressive piece of work is their concept of using the batteries as part of the structure of the car, rather than as something that must be contained in the structure. They explain how they studied plane wings being used as gas tanks. They also show they looked at how production lines operate in other industries, to get new ideas for their factories. How many engineering divisions think like that in competing car companies? Probably not many.

The second factor is how people collaborate rather than working separately. For example, the octovalve’s manifold has a design very similar to printed circuit boards and computer chips. Tesla has those skills in-house, notably after they hired a team from AMD in 2016. This is one of the many evidences of knowledge pollination across their organisation. Another example would be the cooling system for their Dojo supercomputer, for which they used the extensive experience and knowledge of the team having developed the cars cooling system and indeed the octovalve, as Elon explained at the end of 2021 Tesla AI Day event.

Knowledge pollination is an enabler of fast innovation; it requires strong collaboration, which is influenced by the structure of the organisation. In his talk with Sandy Munro, Elon Musk said “the organisation structure errors manifest themselves in the product.” He then goes on to use the wheels and body engineering as an example: “there was lots of engineering done, and there were lots of right answers to the wrong questions. Somebody would say “what’s the best material to make this [or that] little section?” [… and they came up with answers] that were all true individually but not true collectively. [And when all parts are conceived separately, the resulting product] looks a bit like Frankenstein when you look at it altogether.” This reminds us of Conway’s law: any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.

Lack of communication and collaboration is a persistent reality in most traditional companies and indeed visible in Tesla competitors’ organisations through the products they create. In the teardown of the Ford Mustang Mach-e, Sandy Munro’s team found two surprising brackets bolted on the rear structure of the trunk, that serve as bump-up to support a plastic part.

He explains that the plastic part was supposed to fit on the metal sheet, yet it does not, so the brackets had to be added to compensate: “this is what happens when the interior people and the sheet metal people don’t talk to each other at the right time. […] This is what happens when the communication falls off between engineering groups [who] operate in silos.”

How could other organisations improve collaboration to avoid the Frankenstein effect? As David Marquet explains in his books and speeches, it first requires to create an environment where people think. Most traditional organisations poorly use their collaborators’ brain power and talent, people are often told what to do, rather than being told what needs to be achieved and left to think how to best do it. Yves Morieux says it is all about collaboration, about the neural connections in your organisation. Teams need to work as a network, thinking collectively about the whole rather than focusing solely on the parts they are expected to produce. To that, Elon adds “there is another important principle, which is that you really want everyone to be a chief engineer, which means people need to understand the system at high level to know when they are making a bad optimization.” Havin a high level understanding will also help people to understand what others do and how to best collaborate.

What is also needed from leaders is to create an environment where collaborators are neither afraid nor discouraged from speaking up about problems, where challenging existing constraints and processes is welcomed and viewed as healthy and positive. This is seemingly the case at Tesla, with Elon asking all employees to focus on costs, as exemplified in an email: “This a tough Game of Pennies — requiring thousands of good ideas to improve part cost, a factory process or simply the design, while increasing quality and capabilities. A great idea would be one that saves $5, but the vast majority are 50 cents here or 20 cents there.” This shows Tesla CEO considers everyone as part of the Tesla team, and this is a collective effort where everyone can contribute: he recognizes that every brain can come up with good ideas, not just managers.

In a Q&A session, Sandy Munro was asked why Tesla achieved 300miles mileage before other brands. His answer: “because they think ahead”. He then says legacy companies are “slaves of the parts bin”, which from an organisational perspective means teams are asked to use existing parts in order to avoid the costs of acquiring or creating new ones. This very focus on frontal cost/effort reduction through the use of existing parts has sometimes long-term negative impact: design is constrained and teams can’t innovate as much as they could. We see two factors contributing to this situation: the focus on frontal costs constraining innovation and long-term product improvement, and the siloed nature of organisations where parts are optimised but not the whole product -once more, Frankenstein effect-. Looking at short-term gains leading to long term losses because of less performing products, Sandy concludes: “Don’t Save Me Any Money, I Can’t Afford It!”

Fast iterations with “good enough for now”, and 5 engineering steps

In an interview from SpaceX’s Starbase, when describing a mount point, Elon says “it is debatable whether this is the right design or not. In fact, it’s like the whole design is wrong, just a matter of how wrong.” He moves on to say that weight reduction is a moving target, and that “right now, everything is too heavy”. Later on in the video he comments on huge grid fins that help stabilise the rocket trajectory on its re-entry in the atmosphere, he says those are way too heavy but “good enough for now. [..] We’ll make it work, then we’ll optimise it.” About a set of batteries used to action parts of the Starship rocket, Elon says they are currently using energy optimised batteries, made to operate over long time, such as in cars, while what they need for the rocket are power optimised batteries, made to provide high energy over a short lapse of time. He adds: “this is just a short-term thing”, meaning this is good enough for now and will be optimised in next iterations.

The notion of “good enough for now” is a difficult concept for engineers who often tend to perfection. “Good enough for now” goes against the belief that perfection is best achieved through meticulous, exhaustive planning. The trouble is that with complex products it is difficult to foresee all possible problems and points of failure. Agile engineering acknowledges that it is extremely difficult to foresee all risks in complex systems, and that time is better spent learning through iterations of yet unperfect parts than on long upfront planning. On this topic, Elon notes that none of the reasons why Starship prototypes blew up had been flagged in their risk list. None. Testing live as soon as possible with not perfect but “good enough for now” parts is an efficient way to both validate interfaces and discover issues that had not been anticipated.

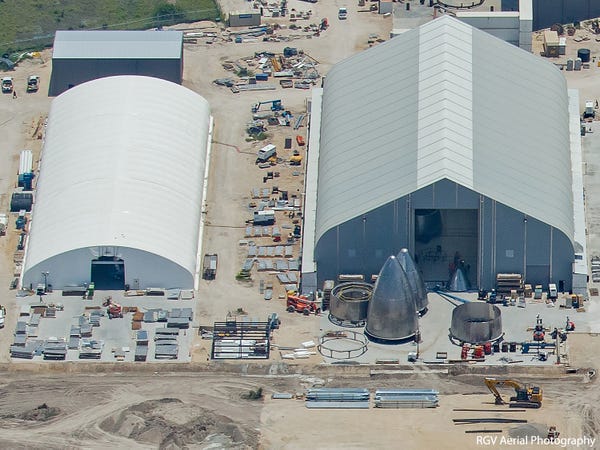

This is what SpaceX have been doing with their rockets, up to their Starship, the most powerful rocket ever designed and built. Many mocked their repeated failures, with rockets exploding one after the other in a high cadence of launches. But with every iteration and failure, SpaceX learnt and improved. They also take time to simply test their interfaces. Overall, these cycles of fast prototyping have enabled them to create reliable rockets in a much shorter time frame than competitors working in traditional ways. The shorten development period and consequently improved time to market have more than compensated the extra costs of building failed prototypes.

In addition to first principles thinking, system design and fast iterations, Elon also talks about what he calls a “rule” he attempts to implement rigorously, comprising 5 ordered steps:

- Make your requirements less dumb, and ensure there is a clear owner to engage with, not something vague like a department or unit

- Try very hard to delete the required part or process, making the system and/or product leaner

- Simplify or optimize the part or process

- Go faster, reduce cycle time to increase the pace of production and/or innovation

- Automate

About the first rule, he comments: “It does not matter who gave [the requirements] to you. It’s particularly dangerous if a smart person gave you the requirements because you might not question them enough. Everyone’s wrong, no matter who you are, everyone’s dumb some of the time.”

On the second one, he uses a practical example around the design of SpaceX Starship rocket, saying that the grid fins are fix rather than foldable, as the extra weight of related mechanism is worse than the drag caused by fix grid fins. He adds: “if you’re not deleting a part or process at least 10% of the time, you’re not deleting enough”.

While talking about the third step, he comments that “possibly the most common error of a smart engineer [is] to optimize the things that should not exist”, emphasizing once more the importance of the second step. This indeed reminds us of Peter Drucker famous quote “There is surely nothing quite so useless as doing with great efficiency what should not be done at all.”

On the fourth step, he mentions the case of in-process testing, where early on many tests are added to spot production defects and improve the line, but often those tests are not later on removed, and therefore negatively impact cycle time.

Elon admits he has multiple times gone backward on those five steps, with poor outcomes. He says he more than once automated, accelerated, simplified, then deleted. He mentions the example of a part of the Tesla model 3 original design, a fiberglass mat that sat on the battery pack, whose related manufacturing process was choking the model 3 production programme. They automated the mat installation, then made the robots work faster. They optimised the quantity of glue used and how it was applied. Only then did they ask “what the hell are those mats for?”. The battery safety team answered it was for noise and vibration, but the team analysing noise and vibration said they were for fire safety… They ended up trying a car with and another without the mat and measured the noise. The results showed no measurable difference, they then removed the mat from the car design and therefore from the manufacturing process.

Elon also mentions what he says is another frequent mistake in manufacturing: too much in-process testing. “When you first set up a production line, you don’t know where the mistakes are, you don’t know where things are breaking, so you’ll test working process at various steps [to] isolate where the mistake is occurring.” But then a common mistake is “to not remove the end process testing after diagnosing where the problems are. So, basically, […] if things are going to end of line testing and are passing, then you do not need to do in-process testing” anymore, and therefore should remove them since they likely impact your cycle time and could become limiting factors when trying to increase production speed.

The factory is the product

Pace of innovation is dependent on how much time is needed to go from idea to production for any product improvement. Tesla build their factories in such a way that speed of change is a focus, resulting in more than 20 changes in average per production line per week, a cadence way faster than most competitors, if not all. Some of their engineering teams work next to the production lines in short iteration cycles of less than half a day, with every cycle potentially resulting in a change on the production line. This is the manufacturing equivalent of DevOps principles and tooling in software development.

At Tesla 2016 shareholder meeting, Elon said: “We realized that the true problem, the true difficulty, and where the greatest potential is – is building the machine that makes the machine. In other words, it’s building the factory. I’m really thinking of the factory like a product. […] I actually think that the potential for improvement in the machine that makes the machine is a factor of ten greater than the potential on the car side.” If valuable improvements are easier to reach in the way we produce our products than in the product itself, then it is certainly pertinent to invest more on improving the productive assets.

And since the factory is considered a product, the same agile approach is applied to its development: iterative with fast feedback loops and learning cycles. As visible on the publicly available images of regular fly-over of all Tesla factories, those are built fast, and iteratively: new additional sections often start as a simple tent with few workers starting first level production, which enables them to learn what works and what does not. The unit then expands with a bigger tent, and later on becomes a full part of the factory, with hard walls and roof. While some experts laughed at those tents, they are one of the reasons why Tesla factories are as good as they are and are built that fast: iterative development with fast learning cycle and improvements.

At the end of the Battery Day presentation, one of the speakers is a Tesla construction manager, he says: “the thing that sets us apart from other construction companies is that we are integrated in the manufacturing process, so every detail […] is directly implicated into the system we build. That way, what would typically take 3 to 4 months to create a specification, our design team is working right with the manufacturing team to allow us to speed up that process tremendously.” Drew Baglino, SVP of Powertrain and Energy Engineering at Tesla, adds: “this is definitely an important part of our vertically integrated approach, to be able to design the factory around the equipment, in fact together with the equipment, so that you can build the factory at lower cost and more quickly.”

We can see there is a virtuous Tesla triptych: agile factory building * agile manufacturing with fast changes and trials * massive amount of useful data collected from their fleet of sold vehicles and analysed with support of AI.

The three parts of this triptych multiply the potential of the others, leading to amazing results. Those are enabled and supported by the company’s culture along the way they work with a system approach and the “first principles”. In the opinion of Sandy Munro, Tesla has no real competition yet, but he says he has seen how new Chinese companies work in a way similar to Tesla, and he expects a “sh*t show” when they enter western markets, with established companies suffering as much as when Japanese car makers entered western market decades ago. He added “if you’re young, go talk to your boss about maybe waking up and doing something a lot better than what we saw with VW ID4.”

Competitors try to catch up

BMW started their Agile transformation after Tesla announced their model 3. Few years ago Renault started to hire many Agile coaches in a push for a nimbler organisation more focused on digital. Jaguar recently started their Reimagine program with a strong push on agility. How genuine is it? Do all those companies’ leaders really understand what it means and takes to do it right? Do they understand it is not just a change of organigram, methods and processes? Time will tell.

Joe Justice participated in 2020 in a call with some of the management from Renault. He asserted that if Renault bought Tesla, ousted the Tesla leadership team only and inserted Renault’s existing leadership team, the pace of New Product Development and New Product Introduction would slow. All attending managers agreed to this speculation. Joe asserts the top leadership team culture sets the pace and psychological safety, and this cadence determines if agile methods or a slow internal chess game are more honoured by the business culture.

Volkswagen’s chairman Herbet Diess wrote that “We’re no start-up – our structures and processes have developed organically over decades. Many are now antiquated and complicated. Above all, we have a range of different interests and political agendas in the Group. […] Things had to change! […] We honed and decentralized hierarchies in Wolfsburg. We reorganized the model series with a more modern structure for the development process to eliminate a bottleneck that was slowing down product decisions. The regions were given more scope to make decisions faster and more relevant to their local market.”

He also wrote “we realized that our corporate structures prevent us matching the development speed and capacities of a well-funded and unbureaucratic start-up like Tesla, with its far greater risk propensity. [… Tesla’s] Silicon Valley-style ecosystem is influenced by software capabilities, focus on technology and risk culture”. And VW got much better results with a new structure created on purpose, outside of the existing historic organisational structure. They see it as success, yet that also is an admission of how difficult and challenging it is to change the rest of the organisation, quite similar to traditional banks who failed at transforming themselves and opted to create new separated structures to host their efforts at competing with new players such as N26, Revolut, Monzo, Starling… And that very fact is going to pull VW and others back for years to come, while Tesla speeds ahead: they need to understand why they struggle to change the main organisation, what rules and structure changes need to happen to evolve the culture, the mindset, and get the company up-to-speed.

It is one thing to decrease the number of layers in an organisation, it is another to foster an environment that encourages people to think and keep improving. Reducing layers and breaking functional silos to create an organisation with cross-functional teams aligned on value streams is painful, stressful for an organisation, yet is not sufficient to get people to better think together. The latter is not a guaranteed consequence of the former. It requires more than changing an organisational structure and work processes; it is about setting an environment that incites people to collaborate, self-organising to create dynamic networks across layers and functions.

Tesla has defied expectations in surviving and growing up to where they are now because of their iterative approach with fast learning continuous improvement, and better collective efforts focused on “first principles” and better system design. They did so with fewer resources. Now, they are financial markets’ darling and have access to nearly unlimited funding. Investors and analysts shall not simply compare cars and individual innovations with competitors’ equivalent. They shall ponder the way Tesla work and operate and how that enables them to do more with less. That is their main competitive advantage, and creates a comparatively higher pace of innovation and adaptation.

Written by Arnaud Viguié with Joe Justice.

Arnaud is an experienced agilist and a Scrum for Hardware trainer, and Joe a hands-on thought leader in hardware agility and the creator of eXtreme Manufacturing.

Joe Justice’s views are his own and all Tesla information shared are already part of the public domain by actions other than Joe’s.

コメント